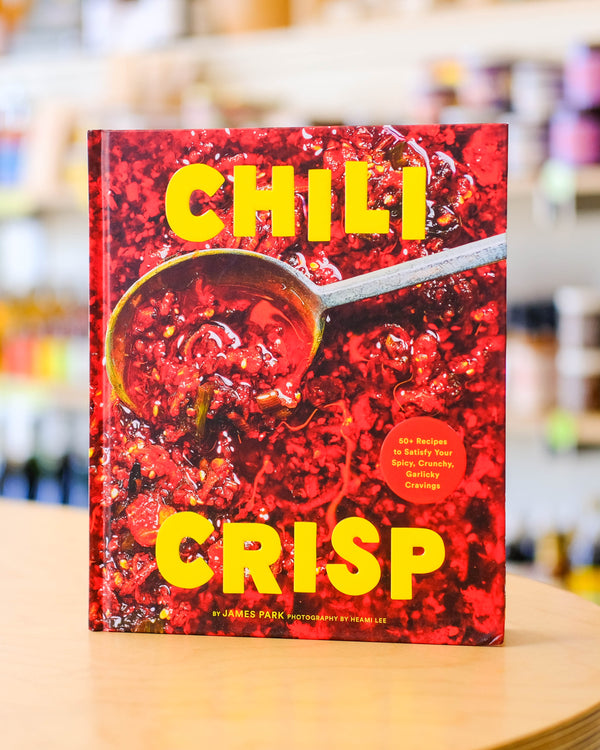

To James Park, chili crisp is personal. It’s more than just a condiment—it allows home cooks to blend the flavors that are meaningful to them, explore and play with food, while learning from Asian ingredients. This interview highlights his upbringing as a Korean American growing up in the South and how he sheds light on the beauty of a blended culture. His amazing book, Chili Crisp: 50+ Recipes to Satisfy Your Spicy, Crunch, Garlicky Cravings, is a guide to exploring your own cultural flavors through a universally loved condiment.

Margot: What was your upbringing like? Was food part of a deeper experience for you?

James: I was born in Korea, but unlike many people who have lots of fond memories of cooking with their moms or grandmas in the kitchen, my mom was never in the kitchen because she was very busy working. Food culture was something that I was kind of lacking growing up in Korea. I was envious of my friends whose moms were always cooking dinner for them. Some of my food memories are through my friends’ moms rather than my own mom. That really became stronger when I came to America.

I came here as an international student when I was thirteen. Because of that young age, I had to live with different host families. I went through several Korean ones, but then I met my current American family who unofficially adopted me. Mrs. Nauman, I call her Princess, really gave me that sense of kitchen memories that I wanted to seek further. Even though she didn't know much about Korean recipes, she showed me how to make roast chicken for the first time and she showed me how to make Caesar salad. I have a lot of American food memories growing up in Alabama. After that, I came to New York and I was able to enjoy all the Korean food that I missed so much.

In Alabama, there was no such thing as H-Mart. All the Korean groceries were behind a gas station in a very janky little store. When I just came to New York, I remember I went to this Korean restaurant in K Town and I saw braised pork feet and fish roe stew, two of my favorite things, but I never thought that I would be able to find that in America, and I was sobbing in happiness.

Food really became a part of my daily life when I became an RA in college and I had access to a kitchen. I would watch Food Network shows and Maangchi for all the Korean recipes, and then cooking became a lot more serious. I saw a path in food media.

Margot: Did you have dreams of becoming a chef?

James: Actually, I always knew that I didn't want to be a chef or work in the restaurant industry, so I was kind of stumped. I didn’t know how to make food into my career. Thankfully, that was when food media was blossoming, thanks to BuzzFeed, and luckily my school also offered a program where I could go to culinary school and get credits. I went to culinary school and the rest is kind of history.

Margot: Did your relationship to food change at all once you moved from Korea?

James: It did. Food became a lot more expressive and a lot more meaningful than when I had food in Korea because in Korea, it's a pretty homogenous community where we would eat Korean food all the time and there was no diversity in the way in America where you think, should we have Thai? Should we have Chinese?

When I grew up in Korea, I didn't really think about what weight a recipe could hold in political America and how personal that is. Kimchi jjigae, for example, it's just something that I ate all the time because that's what my mom would put on the table. I didn't realize that was a perfect vehicle for me to share my immigrant story, share my Korean stories in America.

I realized the role that food can play as I'm figuring out my life and my identity in America and how it's a perfect vehicle for me to connect with other people. I really express a dynamic background that's more than just Korean or a Korean American or, you know, a Southerner.

Margot: How do you use your food to tell a story about your culture or about who you are today?

James: I'm in a very unique situation where I grew up in Alabama. I haven't really met any Koreans who grew up in Alabama. Today, I'm exposed to so many different cultures. There are rules in terms of cooking, but I think when you are cooking with influences that really shaped who you are, it becomes a perfect palette to create the story that you wanted.

Like roast chicken, for example, just something that Princess taught me to make and I wanted to add some sort of a Korean influence to that, to make this more uniquely represent me, show not only my southern roots, but also my introduction to American comfort food—to my Korean comfort foods. Can I make kimchi jjigae with leftovers of roast chicken? Or can I add a little bit of gochujang and a little bit of butter to make that spice? So I think the way I approach my cooking is very boundary-less.

We are in this one big world of culture. How can I bring this part that I really like from other cultures, and this part that I like about Southern American or Korean culture to create something that's very unique that feels special to me, and how can I share that story and flavors of recipes with other people so that they can taste what makes me happy?

A lot of times people go through this identity crisis of like, am I Korean? Am I not Korean? Who am I? Especially for immigrant third culture kids. Showing that you can be really playful with how you're approaching food is important. You don't have to feel so pressured by keeping recipes traditional. I hope that my faithfulness with recipes and cultures and approach to that, while being respectful to the roots, but also thinking outside of the box will help people feel a little more liberated than just putting them into this one dimension of their identity.

Margot: Your book is, Chili Crisp, is focused on one condiment. How does chili crisp fit into your food story?

James: It's a perfect example of me feeling really empowered to express myself. Chili crisp is inherently rooted in Chinese culture. In Korean cuisine, we don't really have anything like that. I didn't really know what chili crisp was until I came to New York. There's a story that I will never forget—one of my favorite things that I used to do was just to go to different grocery stores.

New York has such a vibrant Chinatown. There was a big supermarket where the entire aisle was filled with these red capped bottles. There was like a lady's face in the middle and all kinds of chili crisps and oils. When I first tasted it, it was like, this is so different, but also very familiar.

At the time I was still working through how I understood myself as an immigrant in America. I always thought I had to assimilate to white culture, and I couldn't really celebrate or show off my Asian-ness to succeed in America, especially since I came here without my parents. Chili crisp kind of gave me a way to connect with other Asian communities beyond my Korean people. Some of my Chinese friends taught me how their family used chili crisp and it became a conversation starter.

I was so fascinated by how chili crisp could reunite Asian Americans despite their cultures—whether you're a Korean who grew up in California, or Chinese who grew up in Flushing, they all have memories with iconic bottles of Lao Gan Ma or chili crisp. A few years ago Lao Gan Ma used to be the only brand, but as you know, there have been many other new brands like Fly By Jing and chefs are coming up with their own blend of chili crisps. I was absolutely fascinated by all of them, not only the texture and flavors of the product, but also why they created this chili crisp, why this chili crisp was so personal to them.

I created this collection of everyone's chili crisp, and it was so crazy to taste how each of them—there was no commonality. Even though there was this category of chili crisps, everything was so distinct. I started talking openly about it and got connected with my other chili crisp nerd community out there.

I never felt like I wanted to make my own chili crisp, because it wasn’t part of my Korean upbringing, but I had this amazing opportunity to write a chili crisp cookbook, and as I was working on it, I felt like I needed to make this topic as personal as possible. I needed to think about coming up with my own chili crisp. I have this insecurity of taking this topic that wasn't necessarily mine as some sort of authority as a cookbook author to share this knowledge and love with people. I was a little bit hesitant about what the best angle was to do that.

If I was going to do it, I wanted to share and infuse my Korean flavors and stories, and I came up with this perfect recipe that tasted so Korean, yet so universal and it had all the elements of flavors that I grew up with in New York and the South. Now chili crisp is no longer other people's thing. It is as personal, as important to me as to other Chinese Americans or other people. I felt this safety and this magic of the world of chili crisp—people are so welcoming and curious and I can really taste other people's passions and stories and flavors through all the different ingredients they use.

I didn't know chili crisp was going to be a part of my life like that, but now I really cannot imagine my life without it. And I'm so proud that I wrote this book.

Margot: That's so awesome. I love that. For folks who might just be stumbling upon chili crisp, or stumbling upon your book for the first time, can you talk about what is special about this book?

James: This book gives you a guide to create the stories that you want through cooking. People think that chili crisp is just a condiment, not from their culture. People can be a little intimidated to create their own crisp or use it in their cooking because they don't want to be disrespectful, or they don’t know how to use it beyond just drizzling on top of noodles and dumplings. What made this book so special is that I also felt what they used to feel, and this book allows them to play using delicious recipes from my culture and different cultures that I was exposed to, and also these pep talks really to get people to explore.

If you really like potato chips, if you like the crunch of that, you should explore adding that to create your own blend of chili crisps. Think beyond “what's right”. There's a very fine line of what's appropriation and what's a respectful twist. For a lot of home cooks, cooking can be a way to explore the world beyond their culture, especially when they're cooking something that's different. Chili crisp has the power to transform any dish into something so special and magical, especially if you create your own blend that you're so proud of. I really wanted the book to be that pep talk people need.

I'm really happy with where chili crisp is going and I hope it continuously surprises everyone with all the infinite possibilities it brings.